Rob Portman

Rob Portman | |

|---|---|

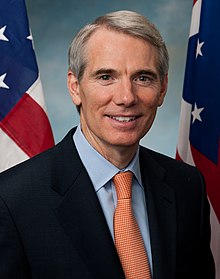

Official portrait, 2018 | |

| United States Senator from Ohio | |

| In office January 3, 2011 – January 3, 2023 | |

| Preceded by | George Voinovich |

| Succeeded by | JD Vance |

| Ranking Member of the Senate Homeland Security Committee | |

| In office February 3, 2021 – January 3, 2023 | |

| Preceded by | Gary Peters |

| Succeeded by | Rand Paul |

| 35th Director of the Office of Management and Budget | |

| In office May 29, 2006 – June 19, 2007 | |

| President | George W. Bush |

| Deputy | Steve McMillin |

| Preceded by | Joshua Bolten |

| Succeeded by | Jim Nussle |

| 14th United States Trade Representative | |

| In office May 17, 2005 – May 29, 2006 | |

| President | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Robert Zoellick |

| Succeeded by | Susan Schwab |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 2nd district | |

| In office May 4, 1993 – April 29, 2005 | |

| Preceded by | Bill Gradison |

| Succeeded by | Jean Schmidt |

| White House Director of Legislative Affairs | |

| In office September 25, 1989 – April 12, 1991 | |

| President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Gordon Wheeler |

| Succeeded by | Stephen Hart |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Jones Portman December 19, 1955 Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Jane Dudley (m. 1986) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Dartmouth College (BA) University of Michigan (JD) |

| Signature | |

Robert Jones Portman (born December 19, 1955) is an American attorney and politician who served as a United States senator from Ohio from 2011 to 2023. A member of the Republican Party, Portman was the 35th director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) from 2006 to 2007, the 14th United States trade representative from 2005 to 2006, and a U.S. representative from 1993 to 2005, representing Ohio's 2nd district.

In 1993, Portman won a special election to represent Ohio's 2nd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives. He was reelected six times before resigning upon his appointment by President George W. Bush as the U.S. trade representative in May 2005. As trade representative, Portman initiated trade agreements with other countries and pursued claims at the World Trade Organization. In May 2006, Bush appointed Portman the director of the Office of Management and Budget.

In 2010, Portman announced his candidacy for the United States Senate seat being vacated by George Voinovich. He easily defeated then-Lieutenant Governor Lee Fisher and was reelected in 2016. On January 25, 2021, he announced that he would not seek a third term in 2022.[1]

After leaving office in 2023, Portman founded The Portman Center for Policy Solutions at the University of Cincinnati.[2] He currently serves as a Distinguished Visiting Fellow in the Practice of Public Policy at the American Enterprise Institute.[3]

Early life

[edit]Portman was born in 1955, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son of Joan (née Jones) and William C. "Bill" Portman II. His family was Presbyterian.[4][5]

In 1926, Portman's grandfather Robert Jones purchased the Golden Lamb Inn in Lebanon, Ohio, and, together with his future wife Virginia Kunkle Jones, refurbished it and decorated it with antique collectibles and Shaker furniture.[7] The couple ran the inn together until 1969, when they retired.[8]

When Portman was young, his father started the Portman Equipment Company, a forklift dealership where he and his siblings worked growing up.[citation needed] From his mother Joan, a liberal Republican, Portman inherited his sympathy for the Republican Party.[9]

Education and early career

[edit]Portman graduated from Cincinnati Country Day School in 1974 and attended Dartmouth College, where he started leaning to the right, and majored in anthropology and earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1978.[10] In Cincinnati, Portman worked on Bill Gradison's congressional campaign, and Gradison soon became a mentor to Portman.[10] Portman next entered the University of Michigan Law School, earning his Juris Doctor degree in 1984 and serving as vice president of the student senate.[11] During law school, he embarked on a kayaking and hiking trip across China and met Jane Dudley, whom he married in 1986.[12] After graduating from law school, Portman moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked for the law firm Patton Boggs. Some describe his role there as a lobbyist; others say that such a description is inaccurate.[13][14][15][16] Portman next became an associate at Graydon Head & Ritchey LLP, a law firm in Cincinnati.[17]

In 1989, Portman began his career in government as an associate White House Counsel under President George H. W. Bush.[18] From 1989 to 1991, he served as Bush's deputy assistant and director of the White House Office of Legislative Affairs.[11] While serving as White House counsel, Portman visited China, Egypt, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.[19]

United States Representative: 1993–2005

[edit]In 1993, Portman entered a special election to fill the seat of Congressman Bill Gradison of Ohio's second congressional district, who had stepped down to become president of the Health Insurance Association of America. In the Republican primary, Portman faced six-term Congressman Bob McEwen, who had lost his Sixth District seat to Ted Strickland in November 1992; real estate developer Jay Buchert, president of the National Association of Home Builders; and several lesser known candidates.

In the primary, Portman was criticized for his previous law firm's work for Haitian president Baby Doc Duvalier.[20] Buchert ran campaign commercials labeling Portman and McEwen "Prince Rob and Bouncing Bob."[20] Portman lost four of the district's five counties, but won the largest, Hamilton County, his home county and home to 57% of the district's population. Largely on the strength of his victory in Hamilton, Portman took 17,531 votes (36%) overall, making him the winner.

In the general election, Portman defeated the Democratic nominee, attorney Lee Hornberger, 53,020 (70%) to 22,652 (29%).[21]

Portman was reelected in 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, and 2004, defeating Democrats Les Mann,[22] Thomas R. Chandler,[23] and then Waynesville mayor Charles W. Sanders four times in a row.[24][25][11]

House legislative career

[edit]

As of 2004, Portman had a lifetime rating of 89 from the American Conservative Union, and ranked 5th among Ohio's 18 House members.[26]

One of Portman's first votes in Congress was for the North American Free Trade Agreement on November 17, 1993.[27]

Of Portman's work on the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998, Pete Sepp of the National Taxpayers Union said, "He set a professional work environment that rose above partisanship and ultimately gave taxpayers more rights."[24] Democratic Representative Stephanie Tubbs Jones from Cleveland said Portman, "compared to other Republicans, is pleasant and good to work with."[28] During the first four years of the George W. Bush Administration, Portman served as a liaison between congressional Republicans and the White House.[28] Portman voted for the Iraq War Resolution in 2002.[29] He was known for his willingness to work with Democrats to enact important legislation.[18]

Portman has said that his proudest moments as a U.S. Representative were "when we passed the balanced budget agreement and the welfare reform bill."[24] As a congressman, Portman traveled to Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait and Mexico.[19] During his time in the House, Portman began assisting prominent Republican candidates prepare for debates by standing in for their opponents in practice debates. He took the role of Lamar Alexander (for Bob Dole in 1996), Al Gore (for George W. Bush in 2000), Hillary Clinton (for Rick Lazio in 2000), Joe Lieberman (for Dick Cheney in 2000), John Edwards (for Cheney in 2004), and Barack Obama (for John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012).[30][31] His portrayals mimic not only the person's point of view but also their mannerisms, noting for instance that he listened to Obama's audiobook reading to study his pattern of speech.[32]

George W. Bush administration: 2005–2007

[edit]United States Trade Representative

[edit]On March 17, 2005, Portman spoke at the White House during a ceremony at which Bush nominated him for United States Trade Representative, calling him "a good friend, a decent man, and a skilled negotiator."[33] Portman was confirmed on April 29[34] and sworn in on May 17.[35][36][37]

Portman sponsored an unfair-trading claim to the World Trade Organization against Airbus because American allies in the European Union were providing subsidies that arguably helped Airbus compete against Boeing. European officials countered that Boeing received unfair subsidies from the United States, and the WTO ruled separately that they each received unfair government assistance.

Portman spent significant time out of the United States negotiating trade agreements with roughly 30 countries, visiting Brazil, Burkina Faso, China, France, Hong Kong, India, Mexico, South Korea, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.[19] During his tenure, he also helped to win passage of the Central American Free Trade Agreement.[38] Portman used a network of former House colleagues to get support for the treaty to lift trade barriers between the United States and Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Honduras. According to The Hill, Portman took his wife, Jane, with him to the Capitol on their wedding anniversary so he could work on the deal.[39]

Hong Kong and trade suit

[edit]

As United States Trade Representative, Portman attended the WTO's Hong Kong conference in 2005. He addressed the conference with a speech on development in Doha, and advocated a 60% cut in targeted worldwide agricultural subsidies by 2010.[40][41] Portman then sponsored a claim against China for extra charges it levied on American auto parts. U.S. steel manufacturers subsequently beseeched the White House to halt an influx of Chinese steel pipe used to make plumbing and fence materials. This was a recurring complaint and the United States International Trade Commission recommended imposing import quotas, noting "the economic threat to the domestic pipe industry from the Chinese surge." With Portman as his top trade advisor, Bush replied that quotas were in the U.S. economic interest. He reasoned the American homebuilding industry used the pipe and wanted to maintain a cheap supply and that other cheap exporters would step in to fill China's void if Chinese exports were curtailed. This occurred at a time when the U.S. steel industry lost $150 million in profit between 2005 and 2007, although China's minister of commerce cited the U.S. industry's "record high profit margins" in the first half of 2004 and continued growth in 2005. China next lobbied Portman to leave matters alone, meeting with his office twice and threatening in a letter that restrictions and what it called "discrimination against Chinese products" would bring "serious adverse impact" to the U.S.-China economic and trade relationship.[42] Portman vowed to "hold [China's] feet to the fire" and provide a "top-to-bottom review" of the U.S.–China trade relationship.[38] His claim that China had improperly favored domestic auto parts became the first successful trade suit against China in the WTO.[38] During Portman's tenure as trade ambassador, the U.S. trade deficit with China increased by 21 percent.[38]

Director of the Office of Management and Budget

[edit]

On April 18, 2006, Bush nominated Portman for Director of the Office of Management and Budget, replacing Joshua Bolten, who was appointed White House Chief of Staff.[43] Portman said that he looked forward to the responsibility, adding, "It's a big job. The Office of Management and Budget touches every spending and policy decision in the federal government". Bush expressed his confidence in Portman, saying, "The job of OMB director is a really important post and Rob Portman is the right man to take it on. Rob's talent, expertise and record of success are well known within my administration and on Capitol Hill."[44] The U.S. Senate confirmed him unanimously by voice vote on May 26, 2006.[45][46]

As OMB director from May 2006 to August 2007, Portman helped craft a $2.9 trillion budget for fiscal year 2008. The Cincinnati Enquirer wrote, "The plan called for making the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts permanent, at a cost of more than $500 billion over the five-year life of the proposal. It requested a hefty increase in military spending, along with reductions in low-income housing assistance, environmental initiatives, and health care safety-net programs."[38][47] Portman is said to have been "frustrated" with the post, calling the budget that Bush's office sent to Congress "not my budget, his budget," and saying, "it was a fight, internally." Edward Lazear of Bush's Council of Economic Advisers said that Portman was the leading advocate for a balanced budget, while other former Bush administration officials said that Portman was the leading advocate for fiscal discipline within the administration.[48]

On June 19, 2007, Portman resigned as OMB director, citing a desire to spend more time with his family and three children.[49] Democratic Chairman of the Senate Budget Committee Kent Conrad expressed regret at Portman's resignation, saying, "He is a person of credibility and decency that commanded respect on both sides of the aisle."[50]

Post-White House career

[edit]On November 8, 2007, Portman joined the law firm Squire Sanders as part of its transactional and international trade practice in Cincinnati, Ohio. His longtime chief of staff, Rob Lehman, also joined the firm as a lobbyist in its Washington, D.C. office.[51][52] In 2007, Portman founded Ohio's Future P.A.C., a political action committee.[53][54] In 2008, he was cited as a potential running mate for Republican presidential nominee John McCain.[55][56][57] Portman remained critical of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, passed while he was out of office.[58]

United States Senator: 2011–2023

[edit]

Elections

[edit]2010

[edit]On January 14, 2009, two days after George Voinovich announced he would not be running for re-election, Portman publicly declared his candidacy for the open U.S. Senate seat.[59][60] Running unopposed in the Republican primary, Portman benefitted substantially from Tea Party support, and by July 2010 had raised more campaign funds than Democrat Lee Fisher by a 9 to 1 margin.[61] Portman campaigned on the issue of jobs and job growth.[62]

Of all candidates for public office in the US, Portman was the top recipient of corporate money from insurance industries and commercial banks in 2010.[62][63] Portman possessed the most campaign funds of any Republican during 2010, at $5.1 million, raising $1.3 million in his third quarter of fundraising.[64]

Portman won the election by a margin of 57 to 39 percent, winning 82 of Ohio's 88 counties.[65] In a 2010 campaign advertisement, Portman said a "[ cap-and-trade bill] could cost Ohio 100,000 jobs we cannot afford to lose;" subsequently, The Cleveland Plain Dealer and PolitiFact called Portman's claim "barely true" with the most pessimistic estimates.[66]

2016

[edit]The 2016 re-election campaign posed several special challenges to Portman and his team—it would be run in heavily targeted Ohio, it would occur in a presidential year when Democratic turnout was expected to peak, and both parties would bombard Ohio voters with tens of millions of dollars in TV, cable and digital ads for the national, senatorial and downticket contests. For his campaign manager, Portman chose Corry Bliss, who had just run the successful re-election of Sen. Pat Roberts in Kansas. Portman and Bliss chose to run what Time magazine called "a hyperlocal campaign without betting on the nominee's coattails."[67]

As Real Clear Politics noted, Portman faced "the thorny challenge of keeping distance from Trump in a state Trump [was] poised to win. Portman, in the year of the outsider, [was] even more of an insider than Clinton ... Yet he [ran] a local campaign focused on issues like human trafficking and opioid addiction, and secured the endorsement of the Teamsters as well as other unions" (despite being a mostly conservative Republican).[68]

Polls showed the race even (or Portman slightly behind) as of June 2016; afterwards, Portman led Democratic ex-Gov. Ted Strickland in every public survey through Election Day. The final result was 58.0% to 37.2%, nearly a 21-point margin for Portman.

Chris Cillizza of The Washington Post argued that the context of Ohio's result had wider implications. "There are a lot of reasons Republicans held the Senate this fall. But Portman's candidacy in Ohio is the most important one. Portman took a seemingly competitive race in a swing state and put it out of reach by Labor Day, allowing money that was ticketed for his state to be in other races, such as North Carolina and Missouri ..."[69]

The Washington Post said "Portman took the crown for best campaign",[69] while Real Clear Politics said, "Sen. Rob Portman ran the campaign of the year.".[70] Portman himself was generous in praising his campaign manager: "With an emphasis on utilizing data, grassroots, and technology, Corry led our campaign from behind in the polls to a 21-point victory. He's one of the best strategists in the country."[71]

Tenure

[edit]

112th Congress

In the 112th Congress, Portman voted with his party 90% of the time.[72] However, in the 114th United States Congress, Portman was ranked as the third most bipartisan member of the U.S. Senate by the Bipartisan Index, a metric created jointly by The Lugar Center and the McCourt School of Public Policy to reflect congressional bipartisanship.[73] During the first session of the 115th Congress, Portman's bipartisanship score improved further, propelling him to second in the Senate rankings (only Senator Susan Collins scoring higher),[74][75] Portman's intellectual leadership among the Senate G.O.P., and his fundraising capabilities,[76] led to his being named the Vice Chairman for Finance of the National Republican Senatorial Committee for the 2014 election cycle.[77] In March 2013, Portman was one of several Republican senators invited to have dinner with President Obama at The Jefferson Hotel in an attempt by the administration to court perceived moderate members of the upper chamber for building consensual motivation in Congress; however, Portman did not attend and instead had dinner with an unnamed Democratic senator.[78]

Portman delivered the eulogy at the August 2012 funeral of Neil Armstrong,[79] and the commencement address at the University of Cincinnati's December 2012 graduation ceremony.[80]

In August 2011, Portman was selected by Minority Leader Mitch McConnell to participate in the United States Congress Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction.[81] During the committee's work, Portman developed strong relationships with the other members, especially Sen. John Kerry and Rep. Chris Van Hollen.[82] The committee was ultimately unsuccessful, with Portman left disappointed, saying "I am very sad about this process not succeeding because it was a unique opportunity to both address the fiscal crisis and give the economy a shot in the arm."[83]

Portman spoke at the May 7, 2011 Michigan Law School commencement ceremonies, which was the subject of criticism by some who opposed his stance on same-sex marriage.[84] He and his wife walked in the 50th anniversary march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge commemorating Bloody Sunday and the March on Selma.[85]

On January 25, 2021, Portman announced that he would not run for a third term in 2022.[86] In a statement, he said he looked forward to "focus[ing] all my energy on legislation and the challenges our country faces rather than on fundraising and campaigning." He added, "I have consistently been named one of the most bipartisan senators. I am proud of that and I will continue to reach out to my colleagues on both sides of the aisle to find common ground. Eighty-two of my bills were signed into law by President Trump, and 68 were signed into law by President Obama." Of why he chose not to seek another term, he said, "I don't think any Senate office has been more successful in getting things done, but honestly, it has gotten harder and harder to break through the partisan gridlock and make progress on substantive policy, and that has contributed to my decision."[87]

Committee assignments[88]

- United States Senate Committee on Finance[89]

- United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources[90]

- United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs[91]

- United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations[92]

- Subcommittee on Europe and Regional Security Cooperation

- Subcommittee on Near East, South Asia, Central Asia, and Counter-Terrorism

- Subcommittee on State Department and USAID Management, International Operations, and Bilateral International Development

- Subcommittee on Multilateral Development, Multilateral Institutions, and International Economic, Energy, and Monetary Policy

Caucus memberships

Portman belonged to the following caucuses in the United States Senate:

- Congressional Serbian American Caucus[93]

- International Conservation Caucus (Co-chair)[94]

- Sportsmen's Caucus[95]

- Senate Ukraine Caucus (Co-chair)[96]

- Senate Artificial Intelligence Caucus (Co-chair)[97]

Political positions

[edit]

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, while in the Senate, Portman portrayed himself as a "deficit hawk" and was "considered a centrist-to-conservative Republican" who has typically voted with the party leadership, although he broke with it on a number of issues, including same-sex marriage.[98] In 2013, Portman was several times described as staunchly conservative.[99][100] During the Trump administration, Portman was characterized as a centrist or moderate Republican.[101][102][103][104] In 2020, Portman's former campaign manager described him as a "proud conservative".[104] Chris Cillizza, writing in 2014, described Portman as more governance-oriented than campaign-oriented.[105]

GovTrack places Portman toward the center of the Senate's ideological spectrum; according to GovTrack's analysis, Portman is the third most moderate Republican in 2017 being to the right of Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski but to the left of his other Republican colleagues.[106] The American Conservative Union gives Portman a lifetime 79% conservative grade.[107] The progressive Americans for Democratic Action gave Portman a 25% liberal quotient in 2014.[107] The non-partisan National Journal gave Portman a 2013 composite ideology score of 71% conservative and 29% liberal.[107]

According to FiveThirtyEight, which tracks congressional records, Portman voted in line with Trump's position on legislation 90.4% of the time.[108] As of October 2022, he had voted with Biden's positions about 61.8% of the time.[109] CQ RollCall, which also tracks voting records, found that Portman voted with President Obama's positions on legislation 59.5% of the time in 2011.[110] He was one of five Senate Republicans who voted with Obama's position more than half the time.[111]

2012 presidential election

[edit]Portman was considered a possible pick for vice president on the Republican presidential ticket in 2012.[112][113][114] Chris Cillizza wrote that Portman's time in both the executive and legislative branches would qualify him for the role.[115]

After Mitt Romney selected Paul Ryan as his running mate, Portman spoke at the 2012 Republican National Convention about trade and his family business.[116] On trade agreements, Portman stated: "President Obama is the first president in 75 years-Democrat or Republican-who hasn't even sought the ability to negotiate export agreements and open markets overseas. Now why is this important? Because 95 percent of the world's consumers live outside our borders. And to create jobs, our workers and our farmers need to sell more of what we make to those people."[116] In October 2012, Romney spoke at and toured Portman's Golden Lamb Inn.[117]

Portman portrayed President Obama in Romney's mock debate sessions for the general election, reprising a role that he played in the debate preparations of Republican presidential nominee John McCain in 2008.[118]

2016 presidential campaign

[edit]In March 2014, Larry Sabato of the University of Virginia Center for Politics speculated that Portman might run for president in 2016.[119][120] In October 2014, students from the College of William and Mary formed the Draft Rob Portman PAC to encourage Portman to run for president in 2016.[121] However, Portman announced in December 2014 that he would not run for president and would instead seek a second term in the United States Senate.[122]

Portman initially endorsed his fellow Ohioan, Governor John Kasich, during the Republican primaries.[123] In May 2016, after Kasich dropped out of the race and Trump became the presumptive Republican nominee, Portman endorsed Trump.[124] After the emergence of old audio recordings where Trump bragged about inappropriately touching women without their consent in October 2016, Portman announced that he was rescinding his endorsement of Trump and would instead cast a write-in vote for Trump's running mate, Indiana Gov. Mike Pence.[125]

2020 campaign, Capitol attack, and Trump impeachments

[edit]In the 2020 presidential election, Portman supported Trump, in a reversal of his 2016 vote.[126] Portman maintained his support for Trump during the impeachment proceedings against Trump for his conduct in the Trump–Ukraine scandal.[127] Portman said that it was "wrong and inappropriate" for Trump to ask a foreign government to investigate a political rival,[128] and that he accepted that there was quid pro quo between Trump and Ukraine in which U.S. aid to Ukraine was on the line,[128] but that he did not consider it to be an impeachable offense.[129][128] Following the Senate trial of Trump, Portman voted to acquit Trump on charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.[130] Portman also opposed proposals to formally censure Trump.[128]

Portman was the Ohio state co-chair of Trump's 2020 re-election campaign.[131] After Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election and Trump refused to concede, Portman initially refused to acknowledge Biden as the president-elect of the United States, although he did acknowledge that it was appropriate for Biden's transition to begin and that, contrary to Trump's false claims, there was no evidence of irregularities that would change the election outcome.[132][133] Portman accepted the election results six weeks after the election, after the December 15 Electoral College vote.[134]

Portman opposed Trump's attempt to overturn the election results,[135] and did not back a last-ditch effort by Trump's Republican allies in Congress to object to the formal counting of the electoral votes from swing states in which Biden defeated Trump.[131] Portman said, "I cannot support allowing Congress to thwart the will of the voters"[131] and voted against the objections.[135] Congress's counting of the electoral votes was interrupted by a pro-Trump mob that attempted an insurrection at the Capitol; Portman said Trump "bears some responsibility" for the attack.[135] After Trump was impeached by the House of Representatives for incitement of insurrection, Portman joined most Republican senators in an unsuccessful motion to dismiss the charges and avoid a Senate impeachment trial on the basis that Trump's term had expired and he had become a private citizen.[135][136] On February 13, 2021, Portman voted to acquit Trump on charges of inciting the January 6 attack on the Capitol.[137]

January 6 commission

[edit]On May 27, 2021, along with five other Republicans and all present Democrats, Portman voted to establish a bipartisan commission to investigate the January 6 United States Capitol attack. The vote failed for the lack of 60 required "yes" votes.[138]

Abortion

[edit]On abortion, Portman describes himself as pro-life. He voted in favor of banning abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy.[139] Portman supports legal access to abortion in cases of rape and incest or if the woman's life is in danger.[140] National Right to Life Committee and the Campaign for Working Families, both anti-abortion PACs, gave Portman a 100% rating in 2018; NARAL Pro-Choice America gives him a 0%, Planned Parenthood, which is pro-choice, gives him a lifetime 4% rating, and Population Connection, another pro-choice PAC, gave Portman an 11% rating in 2002.[107]

In 2013, Portman sponsored a bill that would have made it a federal crime to transport a minor across state lines for an abortion if doing so would circumvent state parental consent or notification laws.[141]

SFC Heath Robinson Honoring Our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act

[edit]In July 2022, Portman voted for the SFC Heath Robinson Honoring Our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act, which would provide care for veterans suffering from diseases caused by burn pit exposure while serving overseas. He put out a press release celebrating his vote,[142] but changed his position when the House returned the final version of the bill to the Senate, and voted against it.[143]

Budget and economy

[edit]Portman is a leading advocate for a balanced budget amendment.[144] Portman worked with Democratic Senator Jon Tester in 2012 to end the practice of government shutdowns and partnered with Democratic Senator Claire McCaskill on an inquiry into the Obama administration's public relations spending.[145] Portman has proposed "a balanced approach to the deficit" by reforming entitlement programs, writing "[r]eforms should not merely squeeze health beneficiaries or providers but should rather reshape key aspects of these programs to make them more efficient, flexible and consumer-oriented."[146] Portman became known for his ability to work in a bipartisan fashion when working to pass a repeal of the excise tax on telephone service.[147] He also unsuccessfully proposed an amendment to the surface transportation reauthorization bill to allow states to keep the gas tax money they collect, instead of sending it to Washington with some returned later.[145] On August 10, 2021, he was one of 19 Republican senators to vote with the Democratic caucus in favor of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.[148] In October 2021, Portman voted with 10 other Republicans and every member of the Democratic caucus to end the filibuster on raising the debt ceiling,[149] but voted against the bill to raise the debt ceiling.[150]

LGBT rights

[edit]While still in the U.S. House, Portman co-sponsored the Defense of Marriage Act, a bill passed in 1996 that banned federal recognition of same-sex marriage;[151] in 1999, he voted for a measure prohibiting same-sex couples in Washington D.C. from adopting children.[152] On March 14, 2013, Portman publicly announced that he had changed his stance on same-sex marriage, and now supported its legalization,[153][154][155] becoming the first sitting Republican U.S. senator to do so.[156] The change came two years after his son Will came out to Portman and his wife as gay in 2011.[157] The Human Rights Campaign (HRC), which supports same-sex marriage and gay rights, gave Portman a 45% score in 2014 and an 85% score in 2016; the HRC also gives Portman a 100% rating for sharing its position on same-sex marriage.[107]

In November 2013, Portman was one of 10 Republican senators to vote for the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), after the Senate adopted an amendment he proposed to expand religious protections.[158]

After the House passed a bill to federally protect gay marriage on July 19, 2022,[159] a press spokesman for Portman said he would cosponsor the bill in the Senate.[160] He cosponsored the bill the following day.[161] He was one of 12 Republicans in the Senate voting to advance and pass the Respect for Marriage Act, the legislation protecting federal same-sex marriage rights into federal law.[162]

Women's rights

[edit]Portman voted for reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act in 2013.[163]

Environment

[edit]In 2011, Portman voted to limit the government's ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, and in 2015, he voted to block the Clean Power Plan.[164][165] In 2013, he voted for a point of order opposing a carbon tax or a fee on carbon emissions.[166] In 2012, Portman said he wanted more oil drilling on public lands.[167] Portman supported development of the Keystone XL pipeline, stating "The arguments when you line them up are too strong not to do this. I do think that at the end of the day the president [Obama] is going to go ahead with this."[168]

In 2013, Portman co-sponsored a bill that would reauthorize and modify the Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Act of 1998 and would authorize the appropriation of $20.5 million annually through 2018 for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to mitigate the harmful effects of algal blooms and hypoxia.[169][170]

Portman co-sponsored an amendment to the 2017 Energy Bill that acknowledged that climate change is real and human activity contributes to the problem.[171]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Portman opposes U.S. ratification of the Convention on the Law of the Sea.[172]

In March 2016, Portman authored the bipartisan bill Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act, along with Democratic Senator Chris Murphy.[173] Congressman Adam Kinzinger introduced the U.S. House version of the bill.[174] After the 2016 U.S. presidential election, worries grew that Russian propaganda on social media spread and organized by the Russian government swayed the outcome of the election,[175] and representatives in the U.S. Congress took action to safeguard the National security of the United States by advancing legislation to monitor incoming propaganda from external threats.[173][176] On November 30, 2016, legislators approved a measure within the National Defense Authorization Act to ask the U.S. State Department to take action against foreign propaganda through an interagency panel.[173][176] The legislation authorized funding of $160 million over a two-year-period.[173] The initiative was developed through the Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act.[173]

Israel

[edit]In 2018 Portman and Senator Ben Cardin co-authored the Israel Anti-Boycott Act, which would make it illegal for companies to engage in boycotts against Israel or Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories. They promoted the bill and sought to integrate it into omnibus spending legislation to be signed by Trump.[177][178][179]

Trade

[edit]Portman supported free trade agreements with Central America, Australia, Chile and Singapore, voted against withdrawing from the World Trade Organization, and was hailed by Bush for his "great record as a champion of free and fair trade."[180][181]

Portman has repeatedly supported legislation to treat currency manipulation by countries as an unfair trade practice and to impose duties on Chinese imports if China does not stop the practice.[182] In 2016, Portman opposed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement because he said it does not address currency manipulation and includes less-strict country-of-origin rules for auto parts.[183] In April 2015, Portman co-sponsored an amendment to Trade Promotion Authority legislation which would require the Obama administration to seek enforceable rules to prevent currency manipulation by trade partners as part of TPP.[184]

In January 2018, Portman was one of 36 Republican senators who asked Trump to preserve the North American Free Trade Agreement.[185]

In November 2018, Portman was one of 12 Republican senators to sign a letter to Trump requesting the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement be submitted to Congress by the end of the month to allow a vote on it before the end of the year; the letter-writers cited concerns that "passage of the USMCA as negotiated will become significantly more difficult" if it had to be approved through the incoming 116th Congress, in which there was a Democratic majority in the House of Representatives.[186]

Gun laws

[edit]Portman has an "A" rating from the NRA Political Victory Fund (NRA-PVF), which has endorsed Portman in past elections.[187][188] According to OpenSecrets, the NRA spent $3.06 million to support Portman between 1990 and 2018.[189]

In 2019, Portman was one of 31 Republican senators to cosponsor the Constitutional Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act, a bill introduced by Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz that would allow persons concealed carry privileges in their home state to also carry concealed weapons in other states.[190]

In 2022, Portman became one of ten Republican senators to support a bipartisan agreement on gun control, which included a red flag provision, a support for state crisis intervention orders, funding for school safety resources, stronger background checks for buyers under the age of 21, and penalties for straw purchases.[191]

Health care

[edit]Portman has worked to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.[192] In 2017, he voted to repeal it.[193] He opposed steep cuts to Medicaid because the expansion of the program had allowed some Ohioans to gain coverage, including some impacted by Ohio's opioid crisis.[194] As a member of a group of 13 Republican senators tasked with writing a Senate version of the AHCA,[195] he supported proposed cuts to Medicaid that would be phased in over seven years.[196][197]

Immigration

[edit]In June 2018, Portman was one of 13 Republican senators to sign a letter to Attorney General Jeff Sessions requesting a moratorium on the Trump administration family separation policy while Congress drafted legislation.[198] In March 2019, he was one of a dozen Republicans who broke with their party, joining all Democrats, to vote for a resolution rejecting Trump's use of an emergency declaration to build a border wall.[199] He later co-sponsored a bill to provide for congressional approval of national emergency declarations.[200]

Portman opposed Trump's Muslim ban, saying the executive order was not "properly vetted" and that he supported the federal judges who blocked its implementation.[201]

Jobs

[edit]In 2014, Portman voted against reauthorizing long-term unemployment benefits to 1.7 million jobless Americans. He expressed concern about the inclusion of a provision in the bill that would allow companies to make smaller contributions to employee pension funds.[202] In April 2014 Portman voted to extend federal funding for unemployment benefits. Federal funding had been initiated in 2008 and expired at the end of 2013.[203]

In 2014, Portman opposed the Minimum Wage Fairness Act, a bill to phase in, over two years, an increase in the federal minimum wage to $10.10 per hour.[204] The bill was strongly supported by President Barack Obama and congressional Democrats, but strongly opposed by congressional Republicans.[205][206][207]

In 2015, Portman voted for an amendment to establish a deficit-neutral reserve fund to allow employees to earn paid sick time.[208]

Judiciary

[edit]

In September 2018, Portman said he would support Trump's nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, saying, "The Brett Kavanaugh I know is a man of integrity and humility". Portman did not call for an investigation by the FBI for sexual assault allegations.[209]

In September 2020, Portman supported a vote on Trump's nominee to fill the U.S. Supreme Court vacancy left by the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg less than six weeks before the 2020 presidential election. In April 2016, Portman said that Obama's nominee to the Supreme Court, who was nominated eight months before the election, should not be considered by the Senate, as it was "a very partisan year and a presidential election year ... it's better to have this occur after we're past this presidential election."[210]

Human trafficking

[edit]Portman has been involved in efforts to end human trafficking.[98] As a member of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, he began investigating sex trafficking in 2015. The investigation found that classified advertising website Backpage was aware that the website was being used to sell young girls for sex. Portman sponsored the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, which clarified sex trafficking laws to make it illegal to knowingly assist, facilitate, or support sex trafficking. SESTA was passed by Congress and signed into law by Trump in April 2018.[211]

Biden administration

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

When Joe Biden was declared the winner of the 2020 presidential election, Portman was one of the few Republicans to say that he would certify the electoral college vote.[citation needed] During Trump's second impeachment trial, Portman said, "I will keep an open mind when deciding whether to convict".[citation needed] He ultimately voted not guilty, but said, "Trump's comments leading up to the Capitol attack were partly responsible for the violence".[citation needed]

Portman was one of the main senators involved in crafting the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure plan that passed the Senate in August 2021.[citation needed]

Electoral history

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rob Portman | 667,369 | 100.00% | |

| Total votes | 667,369 | 100.00% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rob Portman | 2,168,742 | 56.85% | −6.61% | |

| Democratic | Lee Fisher | 1,503,297 | 39.40% | +2.85% | |

| Constitution | Eric Deaton | 65,856 | 1.72% | N/A | |

| Independent | Michael Pryce | 50,101 | 1.31% | N/A | |

| Socialist | Daniel LaBotz | 26,454 | 0.69% | N/A | |

| write-in | Arthur Sullivan | 648 | 0.02% | N/A | |

| Majority | 665,445 | 17.44% | |||

| Total votes | 3,815,098 | 100.00% | |||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rob Portman (incumbent) | 1,336,686 | 82.16% | |

| Republican | Don Eckhart | 290,268 | 17.84% | |

| Total votes | 1,626,954 | 100.00% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rob Portman (incumbent) | 3,118,567 | 58.03% | +1.18% | |

| Democratic | Ted Strickland | 1,996,908 | 37.16% | −2.24% | |

| Independent | Tom Connors | 93,041 | 1.73% | N/A | |

| Green | Joseph R. DeMare | 88,246 | 1.64% | N/A | |

| Independent | Scott Rupert | 77,291 | 1.44% | N/A | |

| write-in | James Stahl | 111 | 0.00% | N/A | |

| Total votes | 5,374,164 | 100.0% | N/A | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

Personal life

[edit]

Portman married Jane Dudley in July 1986.[9] Dudley, who previously worked for Democratic Congressman Tom Daschle, "agreed to become a Republican when her husband agreed to become a Methodist."[216] The Portmans attend church services at Hyde Park Community United Methodist Church.[217][218] The Portmans have three children.[9] Portman still owns the Golden Lamb Inn with his brother Wym Portman and sister Ginna Portman Amis.[219] In 2004, a Dutch conglomerate purchased the Portman Equipment Company. Portman had researched the firm's local acquisitions, stating "It's a concept I've heard described as 'Glocalism.' All these companies are trying to achieve economies of scale. This lets us develop a network and coverage globally. But you can still have the local spirit, the local name and the customer intimacy to accomplish great things."[220] A July 2012 article about Portman stated that in 40 years, his only citation has been a traffic ticket for an improper turn while driving.[221] Portman is an avid kayaker, is fluent in Spanish, and enjoys bike rides.[10][222]

In December 2004, Portman and Cheryl Bauer published a book on the 19th-century Shaker community at Union Village, in Turtlecreek Township, Warren County, Ohio. The book was titled Wisdom's Paradise: The Forgotten Shakers of Union Village.[223]

Awards and honors

[edit]On August 23, 2022, Ukrainian President Volodimir Zelensky awarded Portman the Order of Merit, first class, "For significant personal merits in strengthening interstate cooperation, support of state sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, and significant contribution to the popularization of the Ukrainian state in the world."[224] The Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) honored Portman with several awards during his Senate tenure, including the Friend of UNIS Ukrainian Democracy Award in 2014, the Sevchenko Freedom Award in 2016, and the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2022.[225] In 2022, he received the Star of Ukraine Award from the U.S.-Ukraine Foundation and the Appreciation Award from the United Ukrainian Organizations of Ohio.[226][227]

| Year Received | Award | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Special Congressional Appreciation Award | Small Business Council of America[228] |

| 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018 | Hero of Main Street | National Retail Federation (NRF)[229] |

| 2014 | Margaret Mead Award | International Community Corrections Association (ICCA)[230] |

| 2014 | ABA Justice Award | American Bar Association[231] |

| 2015 | Everyday Freedom Hero | National Underground Railroad Freedom Center |

| 2015 | President's Partnering for Quality Award | Ohio Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities[232] |

| 2015 | Bruce F. Vento Public Service Award | National Park Trust[233] |

| 2015 | Distinguished Service Award | Tax Foundation[234] |

| 2016 | Ohio Liberator Award | Save our Adolescents from Prostitution (S.O.A.P.)[235] |

| 2016 | Major General Charles Dick Award for Legislation Excellence | National Guard Association of the United States[236] |

| 2017 | Jefferson-Lincoln Award | Panetta Institute for Public Policy[237] |

| 2017 | Spirit of Enterprise Award | U.S. Chamber of Commerce[238] |

| 2018 | Congressional Award | American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) |

| 2021 | Champion of Retirement Security Award | Insured Retirement Institute[239] |

| 2022 | Ohio History Leadership Award | Ohio History Connection[240] |

| 2022 | National Order, Gran Cruz (Great Cross) | Embassy of Colombia[241] |

| 2022 | Rob Portman Public Service Leadership Award | Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber[242] |

| 2022 | Lifetime Achievement Award | Association for Career and Technical Education (ACTE)[243] |

| 2024 | Honorary Officer of the Order of the British Empire | United Kingdom Government[244] |

Notes

[edit]- Barone, Michael; Ujifusa, Grant (1993). The Almanac of American Politics, 1994. Washington DC. ISBN 0-89234-058-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Barone, Michael; Ujifusa, Grant (1997). The Almanac of American Politics, 1998. Washington DC. ISBN 0-89234-080-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Michael Barone, Richard E. Cohen, and Grant Ujifusa. The Almanac of American Politics, 2002. Washington, D.C.: National Journal, 2001. ISBN 0-89234-099-1

- "CQ Almanac 1993". Congressional Quarterly Almanac, 49th Edition, 103rd Congress, 1st Session. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. 1994. ISBN 1-56802-020-1.

- "Politics in America, 1992: The 102nd Congress". Congressional Quarterly. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. 1991. ISBN 0-87187-599-3.

References

[edit]- ^ Williams, Jason; Wartman, Scott; Sparling, Hannah K. (January 25, 2021). "Ohio's U.S. Sen. Rob Portman won't run for re-election; Republican cites 'partisan gridlock'". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Reilly, M. B. (February 28, 2023). "Establishment of The Portman Center for Policy Solutions to foster bipartisan dialogue, engagement". UC News. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Sen. Rob Portman Joins the American Enterprise Institute as a Distinguished Visiting Fellow in the Practice of Public Policy". American Enterprise Institute - AEI. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Rob Portman Biography". www.biography.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ "The Loyal Soldier: Is Rob Portman the next vice president?" Cincinnati Enquirer, June 25, 2012. By Dan Horn and Deirdre Shesgreen.

- ^ "History: Overview". The Golden Lamb. goldenlamb.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Virginia K. Jones owned landmark Golden Lamb Inn: Family still owns her 'labor of love'". The Cincinnati Enquirer. May 28, 2004. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ "The Golden Lamb Inn". Historic Lebanon, Ohio. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Meticulous Rob Portman has an adventurous side that led him into politics". The Columbus Dispatch. August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Rob Portman.biography". Biography.com. 2013. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c "PORTMAN, Robert Jones (Rob) - Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress.

- ^ "Cincinnati Kid: Jane Portman". Cincinnati Magazine. September 1, 2012. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (March 2000). "The Dartmouth Caucus" (PDF). Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam. "Rob Portman background". The New York Times. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (July–August 2011). "The Dartmouth Caucus (2011)". Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Markon, Jerry; Crites, Alice (July 16, 2012). "Republican Rob Portman, who could be a vice presidential contender, is a Washington insider". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

'He was not in any classic or normal sense a lobbyist,' said Stuart M. Pape, a Patton Boggs partner who supervised Portman.

- ^ Rob Portman was drawn from 'top notch' law career to public service. August 11, 2012. Sabrina Eaton, The Cleveland Plain Dealer. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, David (February 16, 2003). "Bush Loyalist's New Role Is 'Facilitator' in House". The New York Times. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c "On VP List, Pawlenty & Portman Boast Foreign Policy Heft". RealClearPolitics. July 18, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ a b "McEwen, Portman targeted in campaign commercial". Daily Times. February 18, 1993.

- ^ "Democrats and Republicans Split Races for House Seats in 2 States". The New York Times. May 6, 1993.

- ^ "Ohio GOP picks up 4 Washington seats". The Vindicator. November 9, 1994.

- ^ "Results of Contests For the U.S. House, District by District". The New York Times. November 7, 1996.

- ^ a b c "More Bad News for Democrats". The Weekly Standard. March 15, 2010. Archived from the original on March 11, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Kemme, Steve (September 19, 2004). "Portman vows not to take it easy". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- ^ "2004 ACU House ratings". Federal Legislative Ratings. American Conservative Union.

- ^ "FINAL VOTE RESULTS FOR ROLL CALL 575". United States House of Representatives Roll Call Vote. November 17, 1993. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ a b "Ready for Prime Time President Bush has tapped Ohio's Rob Portman to be the nation's top trade negotiator". Blog.cleveland.com. April 19, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "The Iraq War Vote". VoteView.com. October 11, 2002. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- ^ Zeleny, Jeff (July 3, 2012). "Possible No. 2 to Romney Knows Ways of the Capital". The New York Times.

- ^ Moody, Chris (June 4, 2012). "Potential Romney VP Rob Portman is a method actor of debate prep: 'physical mannerisms, parsing of his voice, everything'". ABC News.

- ^ Zeleny, Jeff (August 27, 2012). "Portman to Reprise Obama Role for Romney Debate Preparation". The New York Times.

- ^ Becker, Liz (March 18, 2005). "Congressman From Ohio Is Chosen For Trade Post". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "Resignation from the House of Representatives" (PDF). Congressional Record. May 2, 2005. pp. H2741 – H2742.

- ^ Office of the White House Press Secretary (May 17, 2005). "President Honors Ambassador Portman at Swearing-In Ceremony". George W Bush -White House Archives. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "President Nominates Rob Portman as United States Trade Representative". White House Archives. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (March 18, 2005). "Congressman From Ohio Is Chosen For Trade Post". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Portman's time in Bush White House a double-edged sword". Cincinnati Enquirer. June 22, 2012. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ Koff, Stephen (August 11, 2012). "Rob Portman's exeperience [sic] as trade representative viewed as strength and weakness". The Cleveland Plain Dealer. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ Maidment, Paul. Rob Portman, Take A Bow. Forbes. October 11, 2005.

- ^ "WTO Doha Round: Agricultural Negotiating Proposals" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress.

- ^ Koff, Stephen (August 11, 2012). "Rob Portman's exeperience [sic] as trade representative viewed as strength and weakness". The Cleveland Plain Dealer. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Bush taps Portman to head OMB, Susan Schwab as trade chief". The Financial Express. April 19, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Bush Taps Portman as OMB Chief, Says Rumsfeld Should Stay Portman". FoxNews.com. April 18, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Budget Director Confirmed". Sun Journal. May 27, 2006.

- ^ "Panel clears Portman for budget post". The Wall Street Journal. May 23, 2006. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Press Briefing by OMB Director Rob Portman on the President's Fiscal Year 2008 Budget". The White House. February 5, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Possible VP pick Rob Portman was 'frustrated' at Bush budget office". The Hill. August 2, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Bush Names Ex-Rep. Nussle Budget Chief". The Washington Post. June 20, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Wingfield, Brian (June 19, 2007). "Portman Departs White House Post". Forbes. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Rob Portman to Join Squire, Sanders & Dempsey L.L.P." (Press release). Squire, Sanders & Dempsey L.L.P. November 8, 2007. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ "Portman's top adviser took a hefty pay cut through the revolving door". LegiStorm. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ Riskind, Jonathan (April 10, 2008). "Weighing 2010 contest, Portman names former aide to run PAC". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ "Discuss Ohio's Future with Rob Portman on his blog", OhiosFuture.com, undated

- ^ Novak, Robert (March 28, 2008). "Portman for VP". Townhall.com. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "Barack Obama and John McCain Begin the Search for Running Mates". Fox News. May 27, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ Auster, Elizabeth (April 18, 2008). "Rob Portman: GOP vice presidential candidate?". Cleveland.com. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "Portman Blasts Stimulus, Touts Tax Cuts". Bing Videos. October 13, 2010. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- ^ Rulon, Malia; Whitaker, Carrie (January 14, 2009). "Portman makes it official". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012.

- ^ Hallett, Joe (January 14, 2009). "Portman enters Senate race | Columbus Dispatch Politics". Dispatchpolitics.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Geraghty, Jim (August 17, 2010). "Could Rob Portman Have a 9-to-1 Cash Advantage in Ohio's Senate Race?". National Review. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "Rob Portman's Business Ties Don't Bother Ohio". BloombergBusinessweek. October 28, 2010. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ "Rachel Maddow examines Dan Coates & Rob Portman's 'Tea Party' cred". MSNBC. November 3, 2010. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ Kraushaar, Josh. Cha-ching! Campaign cash tops and flops, Politico, October 16, 2009

- ^ "Senator Portman, U.S. Senator from Ohio – Official Page". portman.senate.gov. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "Portman uses outdated context to claim cap-and-trade could cost 100,000 Ohio jobs". The Cleveland Plain Dealer. July 6, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Elliott, Philip and Newton-Small, Jay, Time, April 13, 2016, "Why Republicans Are Looking Farther Down the Ballot," accessed thru "2016 Elections: Republicans Look Down Ballot". April 14, 2016.

- ^ Real Clear Politics, November 6, 2016, "Things we know at a moment of uncertainty," accessed thru "Things We Know at a Moment of Uncertainty | RealClearPolitics".

- ^ a b Cillizza, Chris (December 21, 2016). "The best candidate of 2016". The Washington Post.

- ^ Real Clear Politics, "Things We Know at a Moment of Uncertainty | RealClearPolitics".

- ^ Altimari, Daniela, Hartford Courant, December 21, 2016, "Bliss a Big Winner of 2016 Cycle," accessed thru "Bliss a Big Winner of 2016 Cycle - Hartford Courant". December 21, 2016.

- ^ "Rob Portman (R)". The U.S. Congress Votes Database. The Washington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ The Lugar Center - McCourt School Bipartisan Index (PDF), The Lugar Center, March 7, 2016, retrieved April 30, 2017

- ^ "The Lugar Center - McCourt School Bipartisan Index" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: The Lugar Center. April 24, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Who is the most bipartisan in Congress? Ohio Sen. Rob Portman near the top, report shows, Cincinnati, Ohio: Cincinnati.com, April 25, 2018, retrieved July 2, 2018

- ^ "Do you have Rob Portman's cell? These donors do". The Cincinnati Enquirer. May 26, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "National Republican Senatorial Committee Leadership". NRSC. March 2014. Archived from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ "Portman missed Obama dinner, met with Dem senator instead". The Cincinnati Enquirer. March 7, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Sen. Portman to deliver eulogy at Neil Armstrong funeral." www.cleveland.com, August 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "December Commencement Ceremony at the University of Cincinnati". University of Cincinnati. December 15, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Ifill, Gwen (August 10, 2011). "Sens. Toomey, Portman Named to Super Committee". NationalJournal.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Spotlight is on Ohio's Low-Profile Portman". Associated Press. June 21, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Torry, Jack (November 27, 2011). "Golden Opportunity Wasted When Supercommittee Failed". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ Troy, Tom (April 21, 2011). "Portman pick draws fire at UM law school". The Toledo Blade. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Portman Statement on Attending the Selma 50th Anniversary". portman.senate.gov. March 7, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ Everett, Burgess (January 25, 2021). "Rob Portman won't seek reelection". Politico. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Kadar, Dan. "Rob Portman: Read Ohio Senator's statement on why he's not running again". The Enquirer. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Committee Assignments - About Rob - Rob Portman". www.portman.senate.gov. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "Membership | The United States Senate Committee on Finance". www.finance.senate.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Subcommittees - U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources". www.energy.senate.gov. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "About the Senate Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs | Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee". www.hsgac.senate.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Committee Membership | United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations". www.foreign.senate.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Portman Joins Congressional Serbian American Caucus". Press Release. Senator Rob Portman. June 7, 2012. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Senate ICC member list" (PDF). U.S. Congressional ICC. International Conservation Caucus Foundation. June 28, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Congressional Sportsmen's Caucus". Congressional Sportsmen's Foundation. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Portman and Durbin Launch Senate Ukraine Caucus". Rob Portman United States Senator for Ohio. February 9, 2015. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ "New Session Sparks New Priorities for Senate AI Caucus". NextGov. January 21, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Gregory Lewis McNamee (December 15, 2020). "Rob Portman". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Dana Bash (March 15, 2013). "One conservative's dramatic reversal on gay marriage". CNN.

[Portman has] been a leading Republican voice on economic issues for four decades...the prominent Ohio conservative...Though he is a staunch conservative, Portman

- ^ Richard Socarides (March 15, 2013). "Rob Portman and His Brave, Gay Son". New Yorker.

Portman is not only a staunch conservative but also an important member of the Republican Party establishment

- ^ Zanona, Melanie (October 7, 2020). "'It wasn't wise': Republicans urge Trump to restart Covid talks". Politico. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Siddons, Andrew (June 9, 2017). "Senate Moderates Say They Are Closer on Health Care". Roll Call. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Weaver, Dustin (May 8, 2017). "What moderate GOP senators want in ObamaCare repeal". The Hill. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Gomez, Henry (October 26, 2020). "Ohio Democrats Want To Make Their Republican Senator The Next Susan Collins". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris (December 2, 2014). "Rob Portman would probably be a good president. He'd never get elected though". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Robert "Rob" Portman, Senator for Ohio - GovTrack.us". GovTrack.us. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Rob Portman's Ratings and Endorsements". votesmart.org.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron. "Tracking Congress In The Age Of Trump". FiveThirtyEight. New York City: New York Times Company. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Bycoffe, Anna Wiederkehr and Aaron (April 22, 2021). "Does Your Member Of Congress Vote With Or Against Biden?". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Ohio Republicans say Sherrod Brown has voted with Obama 95 percent of the time". PolitiFact. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Lesniewski, Niels; Lesniewski, Niels (February 4, 2014). "Collins, Murkowski Most Likely Republicans to Back Obama". Roll Call. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Larison, Daniel (February 2, 2012) Portman Is The Most Likely Selection for VP, The American Conservative

- ^ Memmott, Mark (August 7, 2012). "One Clue To Romney's Veep Pick: Whose Wiki Page Is Getting The Most Edits?". NPR.

- ^ "Why Rob Portman Will Be Romney's Vice Presidential Nominee". The Atlantic. April 5, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ Chris Cillizza (July 17, 2012). "The Case for Rob Portman to be vice president". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ a b "Rob Portman Speech At 2012 Republican National Convention Takes Aim At Obama." The Huffington Post. August 28, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- ^ "Mitt Romney visits Rob Portman's 'haunted hotel'". Yahoo! News. October 13, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- ^ Dana Bash (October 3, 2012). "Romney's sparring partner offers glimpse into GOP debate prep". CNN. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ "Portman For President?". Sabato's Crystal Ball. March 6, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ^ "Republicans Need a Champion in 2016". Politico Magazine. March 3, 2014. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ^ "A Couple of Frat Guys are Behind 'Draft Rob Portman'". Bloomberg. November 16, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ Hagen, Lisa; Railey, Kimberly (January 18, 2015). "The Congressional Tease Caucus: 9 Members Who Think (but Never Act) on Running for Higher Office". National Journal. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Isenstadt, Alex (January 9, 2016). "Rob Portman endorses John Kasich". Politico. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Garbarek, Ben (May 9, 2016). "Rob Portman endorses Donald Trump". ABC 6 On Your Side. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Tobias, Andrew J. (October 9, 2016). "Rob Portman rescinds endorsement of Donald Trump". Cleveland.com. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Balmert, Jessie (January 31, 2019). "Ohio Sen. Rob Portman supports President Trump's 2020 bid - a reversal from 2016 vote". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Eaton, Sabrina (October 29, 2019). "Sen. Rob Portman still plans to vote for President Donald Trump despite impeachment inquiry". Cleveland.com. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Darrel Rowland, Ohio GOP Sen. Rob Portman explains why he backs Donald Trump during impeachment Archived January 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Columbus Dispatch (February 4, 2020).

- ^ Sabrina Eaton, Sen. Rob Portman still plans to vote for President Donald Trump despite impeachment inquiry, (October 29, 2019).

- ^ Sabrina Eaton, Ohio's Sen. Sherrod Brown votes to convict Trump; Sen Rob Portman votes to acquit: watch and read their statements, Cleveland.com (February 5, 2020).

- ^ a b c Rick Rouan; Marc Kovac (January 5, 2021). "Portman won't back Trump bid to toss election results as Ohioans ready buses to DC protest". The Columbus Dispatch.

- ^ Eaton, Sabrina (December 1, 2020). "Sen. Rob Portman still won't call Joe Biden "President-elect"". Cleveland.com.

- ^ Wartman, Scott (December 1, 2021). "Rob Portman won't call Biden president-elect just yet. 'The recounts need to be completed.'". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- ^ Horn, Dan (December 15, 2020). "Ohio Sen. Rob Portman and Rep. Steve Chabot accept election results, but many other Republicans silent". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- ^ a b c d Emily DeCiccio (January 28, 2021). "GOP Sen. Rob Portman says Trump impeachment trial post-presidency could set a dangerous precedent". CNBC.

- ^ Andy Chow (January 26, 2021). "Portman Joins Most GOP Senators In Failed Attempt To Dismiss Impeachment Trial". Statehouse News Bureau.

- ^ "Live impeachment vote count: How senators voted to convict or acquit Trump - Washington Post". The Washington Post.

- ^ Republican senators torpedo Jan. 6 commission, Roll Call, Chris Marquette, May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Portman Votes to Protect Life, Supports Pain Capable Unborn Child Protection Act - Press Releases - Newsroom - Rob Portman". www.portman.senate.gov. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Dispatch, Jessica Wehrman, The Columbus. "U.S. Senate race: Where Rob Portman, Ted Strickland differ on hot-button issues". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sen. Rob Portman says abortion clinics market their services to minors in states with stricter laws". PolitiFact. January 24, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ "Portman Applauds Senate Passage of Bipartisan Legislation to Support our Veterans". Senator Rob Portman. June 16, 2022. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "Senate Republicans block legislation named after Ohio soldier meant to help veterans exposed to toxic burn pits". wkyc.com. July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Frank (2011). "Portman, other Republicans propose balanced budget amendment". Portsmouth Daily Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Almanac of American Politics 2014, p. 1299.

- ^ Portman, Rob (December 10, 2012). "A Truly Balanced Approach to the Deficit". The Wall Street Journal. New York City. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ "Sen. Rob Portman". National Journal Almanac. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ^ Farrington, Dana (August 10, 2021). "Here Are The Republicans Who Voted For The Infrastructure Bill In The Senate". NPR. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ Paul LeBlanc (October 8, 2021). "Here are the 11 Senate Republicans that joined Democrats to break the debt limit deal filibuster". CNN. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Meyer, Mal (October 8, 2021). "Sen. Collins joins vote to break filibuster, but against $480B increase to debt ceiling". WGME. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Reilly, Mollie (March 15, 2013). "Rob Portman Reverses Gay Marriage Stance After Son Comes Out". HuffPost. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "H Amdt 356 – Adoption Restriction Amendment – Key Vote". Project Vote Smart. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ Memoli, Michael A. (March 15, 2013). "GOP Sen. Rob Portman announces support for same-sex marriage". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Abad-Santos, Alexander (March 15, 2013). "GOP Senator Rob Portman Gives His Support to Same-Sex Marriage". The Atlantic. The Atlantic Wire.

- ^ Cirilli, Kevin (March 15, 2013). "Rob Portman backs gay marriage after son comes out". Politico.

- ^ "Gay Marriage Foes Yet to Prove Formidable Threat to Rob Portman". NBC News. November 17, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Stunner: Sen. Rob Portman backs same-sex marriage". CBS News. March 15, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (November 7, 2013). "HISTORIC: SENATE PASSES ENDA". Washington Blade.

- ^ "Roll Call 373, Bill Number: H. R. 8404, Respect for Marriage Act, 117th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. clerk.house.gov. July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Eaton, Sabrina (July 19, 2022). "House passes bill to codify gay marriage over Republican objections led by Ohio's Jim Jordan". cleveland. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ "Cosponsors - S.4556 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Respect for Marriage Act". congress.gov. July 19, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ Metzger, Bryan. "12 Republican senators broke with their party and voted for a bill to protect same-sex marriage". Business Insider. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "Senate roll vote on Violence Against Women Act". Yahoo! News. February 12, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 114th Congress - 1st Session, Vote Number 307, November 17, 2015. "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 114th Congress - 1st Session".

- ^ U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 112th Congress - 1st Session, Vote Number 54, April 6, 2011. "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 112th Congress - 1st Session".

- ^ U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 113th Congress - 1st Session, Vote Number 59, March 22, 2013. "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 113th Congress - 1st Session".

- ^ "Rob Portman claims oil production on public lands was down 14% in 2011: Politifact Ohio". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio: Advance Media Publications. December 31, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Portman: Keystone pipeline would help Ohio". The Columbus Dispatch. 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ "CBO – S. 1254". Congressional Budget Office. May 23, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ Marcos, Cristina (June 9, 2014). "This week: Lawmakers to debate appropriations, VA, student loans". The Hill. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ "These Republican Lawmakers Are Turning To Climate Action To Help Keep Their Seats". ThinkProgress. April 28, 2016.

- ^ Wright, Austin (July 16, 2012). "Law of the Sea treaty sinks in Senate". Politico. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Timberg, Craig (November 30, 2016). "Effort to combat foreign propaganda advances in Congress". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ Kinzinger, Adam (May 10, 2016). "H.R.5181 - Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act of 2016". Congress.gov. United States Congress. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ White, Jeremy B. (September 6, 2017). "Facebook sold $100,000 of political ads to fake Russian accounts during 2016 US election". The Independent.

- ^ a b Porter, Tom (December 1, 2016). "US House of representatives backs proposal to counter global Russian subversion". International Business Times UK edition. New York City: IBT Media. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ "Why These Democratic Presidential Hopefuls Voted No on an anti-BDS Bill". Haaretz. February 11, 2019.

- ^ "Don't Punish US Companies That Help End Abuses in the West Bank". Human Rights Watch. December 18, 2018.

- ^ Grim, Ryan; Emmons, Alex (December 4, 2018). "Senators Working to Slip Israel Anti-Boycott Law Through in Lame Duck". The Intercept. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ "Rob Portman Gets Blasted for Free Trade Record". Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Remarks by the President at Swearing-In Ceremony for the United States Trade Representative". U.S. Department of State. May 17, 2005. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Rob Portman, a former trade chief, will vote to treat China currency manipulation as trade violation". Cleveland.com. October 5, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "Republican Senator Portman opposes TPP trade deal in present form". Reuters. February 4, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "Senate rejects automaker bid on currency manipulation". The Detroit News. April 22, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ Needham, Vicki (January 30, 2018). "Senate Republicans call on Trump to preserve NAFTA". The Hill.

- ^ Everett, Burgess. "GOP senators seek quick passage of Mexico-Canada trade deal". Politico. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018.

- ^ "NRA-PVF "A" Rated and Endorsed Rob Portman". nrapvf.org. NRA-PVF. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018.

- ^ "Ohio". NRA-PVF. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Jessica Wehrman (February 15, 2018). "NRA spent millions to keep Ohio Sen. Portman in office". Dayton Daily News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Sens. Cruz, Cornyn file Concealed-Carry Reciprocity Bill" (Press release). January 10, 2019.

- ^ Bash, Dana; Raju, Manu; Judd, Donald (June 12, 2022). "Bipartisan group of senators announces agreement on gun control". CNN. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ Shesgreen, Deirdre (June 9, 2017). "Rob Portman's dilemma: How to repeal Obamacare without undermining opioid fight". USA Today. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Parlapiano, Alicia (July 25, 2017). "How Each Senator Voted on Obamacare Repeal Proposals". The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Hellmann, Jessie; Weixel, Nathaniel (May 23, 2017). "GOP senators bristle at Trump's Medicaid cuts". The Hill. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Pear, Robert (May 8, 2017). "13 Men, and No Women, Are Writing New G.O.P. Health Bill in Senate". The New York Times.

- ^ Boubein, Rachel; Sullivan, Peter (June 7, 2017). "Key GOP centrists open to ending Medicaid expansion". The Hill. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Torry, Jack (June 10, 2017). "Portman wants phaseout of Medicaid-expansion funds; Kasich has backed in past". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "13 GOP senators ask administration to pause separation of immigrant families". The Hill. June 19, 2018.

- ^ Cochrane, Emily; Thrush, Glenn (March 14, 2019). "Senate Rejects Trump's Border Emergency Declaration, Setting Up First Veto". The New York Times.

- ^ Portman, Rob. "Rob Portman". www.congress.gov. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Timmons, Heather (January 29, 2017). "The short (but growing) list of Republican lawmakers who are publicly condemning Trump's "Muslim ban"". Quartz. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Delaney, Arthur (February 6, 2014). "Unemployment Insurance Extension Fails Again In Senate". HuffPost. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Lowery, Wesley (April 7, 2014). "Senate passes extension to unemployment insurance, bill heads to House". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "S. 1737 – Summary". United States Congress. April 2, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ Sink, Justin (April 2, 2014). "Obama: Congress has 'clear choice' on minimum wage". The Hill. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Bolton, Alexander (April 8, 2014). "Reid punts on minimum-wage hike". The Hill. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Bolton, Alexander (April 4, 2014). "Centrist Republicans cool to minimum wage hike compromise". The Hill. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ "Senate passes budget after lengthy, politically charged 'Vote-a-rama'". The Washington Post. March 27, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Portman Statement Following Today's Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing". portman.senate.gov (Press release). September 27, 2018.